Is Open Banking Helping the Underserved?

11 min read

What it’s about: Open banking is meant to generate new benefits and opportunities for economies and societies. We do not yet have systems to measure who is benefiting from open banking implementations around the globe. This post proposes some new ways to measure the benefits of open banking for all consumer segments.

Why it’s important: Unless we measure how the benefits of open banking are distributed, we risk replicating the inequalities observed in traditional banking systems. Because APIs help enable business growth at speed and at scale, the risk is also that this inequality happens faster and with further reach.

Last updated: 16 December 2020

Open Banking should benefit everyone

There are three consumer segments that have been traditionally under-served by the bank sector. These are:

- Low income consumers in low and middle income countries

- Low income and disenfranchised consumers, including some small businesses, in higher income countries

- Women, migrants, and non-white populations around the globe.

Low income consumers in low and middle income countries

Young people, rural citizens, unemployed, self-employed, and women-led households have often been sidelined by banks in low and middle income countries and are presented with multiple hurdles to opening bank accounts. As a result, consumers have relied upon telecommunications (“telcos”) and payments aggregation industry players to store money in digital accounts and to transfer payments directly from their ‘digital wallets’ to save money, pay bills, top-up their mobile accounts, and shop online.

New open banking regulations in some countries aim to address the needs of these consumer segments. Indonesia, for example, is introducing open banking and open finance regulations that specifically aim to reduce financial exclusion for these consumer segments. As regulations come into play, fintechs in Indonesia that are already serving unbanked populations, including in rural areas, are expected to expand. Indonesian banks are opening APIs that fintech are then using to build products. Customers are opening bank accounts and using their digital wallet apps direct from the fintech app rather than switching to a bank account app. APIs are also enabling customers without credit histories to use their account transaction data to demonstrate credit worthiness.

Low income consumers, including small businesses, in higher income countries

Small businesses and sole traders, single parent families, students, young people, recently arrived migrants, and low income households are some of the consumer segments in higher income countries that do not have bank accounts. There are an estimated 60 million unbanked consumers worldwide in high income countries. The United States, for example, has one of the lowest rates of bank account ownership amongst higher income countries, with 16.3 million adults estimated to be unbanked. Japan is estimated to have 3.7 million adults, and France has 1.8 million adults, without formal bank accounts.

In addition to the unbanked, there are an estimated 20% of consumers who may be underbanked. These consumers have been unable to access credit or to utilise a wider range of banking services due to a lack of bank transaction history. As a result, they do not have full access to a range of banking services to meet their needs.

The expansion of open banking systems should seek to improve access to financial services for these consumer segments. With the impacts of COVID-19 now, and the future challenges from climate risks facing many societies around the globe, improving access to financial resources for all consumers can help reignite local economies and spur new multiplier effects by unlocking growth in looked-over consumer markets.

Fintech businesses are beginning to build apps with open banking APIs to respond to these target markets. Open banking APIs are:

- Creating saving apps and payment by instalment services

- Enabling small businesses to demonstrate their low credit risk through account history data analytics

- Encouraging first time investors to invest or trade, and

- Generating new platforms for real estate investment.

To access many of these new services, previously unbanked or underbanked consumers are opening bank accounts digitally, often using digital identity APIs provided either by banks or governments.

Women, migrants, and non-white populations

While making up half of the world’s population, women have often been marginalised by traditional banking systems.

The idea of open banking is to disrupt these traditional exclusionary practices by introducing a new wave of fintech that can use open banking APIs to build apps that serve those locked out of banking finance systems. Instead, many fintech ecosystems around the globe have only replicated the previous gendered access barriers. While there was hope that open banking and fintech will sweep away traditional male-dominated markets, in this new industry those same patterns of imbalance are playing out again. Today, women make up around 20% of the total number of fintech executive roles globally. This flows through to investment in women-led businesses and it is challenging to get global data on the amount of financing that is directed towards women entrepreneurs. Over the past several years, the average size of business loans for women has been 31% less than for male-owned businesses. Metrics are not yet able to calculate whether open banking is having an effect on these entrenched banking system inequalities.

Similarly, Black people in the United States and Europe, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander populations in Australia, and newly arrived migrants in many parts of the world face systemic barriers to opening bank accounts and accessing finance. US banking group Citi, which hosts open API platforms around the globe, estimates that U.S. Gross Domestic Product has lost $USD16 trillion over the last 20 years predominantly due to lack of lending to Black entrepreneurs. Citi’s study also found that $USD5 trillion could be added to the US economy over the next five years by addressing this gap, along with income inequality, education access and housing credit access for Black homeowners. While Citi is investing $USD1 billion in initiatives that could be driven in part through API-enabled infrastructures, there is a lack of data more widely on the impact that open banking fintech is having on reducing such gaps.

For example, recent government support payments for small businesses in the UK and U.S. were shown to reject Black and minority-owned businesses at a much higher rate than white counterparts. While some banks did leverage their API architectures to speed up government financial support applications, it is unclear whether open banking APIs created greater equity of access to financial support for all business owners.

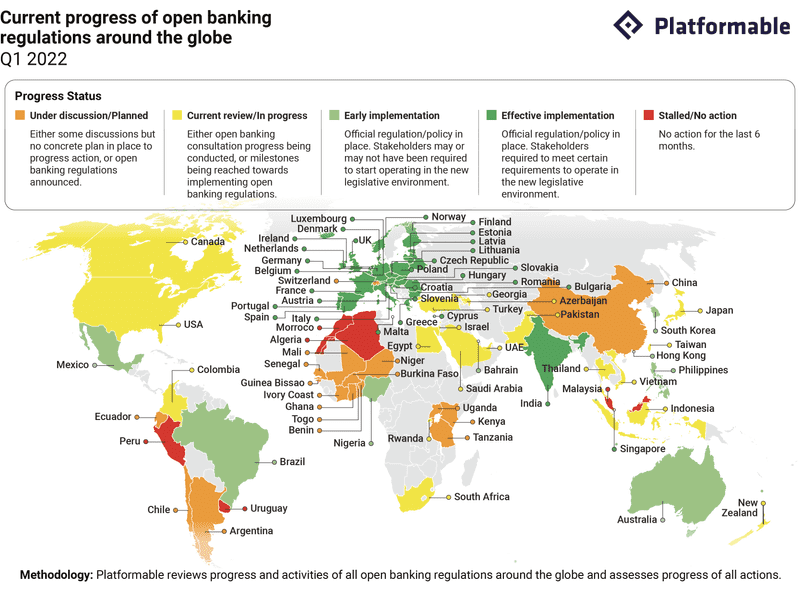

To date, open banking systems are measuring uptake of participation by new fintech market entrants, and the types of products that are becoming available. There are limited frameworks that measure the value flow of open banking systems to disrupt and reduce many of the entrenched imbalances that occurred with previous banking regimes. Some open banking regulations around the globe specifically identify a goal of reducing financial inclusion, and several describe objectives to improve financial health and wellbeing of consumers and small businesses. But at present, there are limited tools available to help regulators, banks and fintech stakeholders to measure the impacts that open banking is having on end consumers.

Creating a data system that measures the impact of open banking on underserved populations

Building on the work of Faith Reynolds and Mark Chidley documented in the Open Banking Consumer Report from the UK, at Platformable we have been starting to map the datasets that would be useful for measuring the benefits that flow to consumers and the underserved (that is, the unbanked and underbanked). We are also building on work that we have done with John Musser for the Consultative Group to the Assist the Poor, where we built an API Dashboard to track the availability of open finance APIs available to support building fintech apps. At present, Platformable is working on updating our 5 wins data model to identify the key datasets that would be helpful for understanding whether open banking is creating value for end consumers.

Some of the explicitly stated goals of open banking regulations around the world are shown in the table below.

Goal

Increase interoperability across borders

Increase consumer choice

Improve financial inclusion

Regulation

Second Payments Services Directive

UK Open Banking, Brazil Open Banking Regulation, and others

Blueprint for Open Banking 2025

Region

Europe

UK, Brazil, Europe, Singapore

Indonesia, Brazil, Mexico, and others

We suggest a starting point is that regulators collect data themselves, or should collate available data from broader datasets (which may also need changing to add more granularity).

Interoperability across borders

Potentially relevant datasets:

- Number of cross-border payments made via open banking APIs

- Average fee to consumers in apps and services that rely on open banking APIs to send money to family in low and middle income countries

- In Europe: Ease with which citizens and businesses can open bank accounts or receive income from work performed across Europe by using fintech apps built with open banking APIs

- Number of fintech apps that can be integrated with a bank account and used across European borders

Increased consumer choice

Potentially relevant datasets:

- Use the limited/emerging/good availability categories as proposed by Reynolds and Chidley. They identified key consumer segments and then categorised available fintech apps in the UK market in terms of availability in meeting the needs of each of these consumer segments. Platformable has used a similar model when describing availability of apps in our Open Banking APIs: State of the Market 2020 Report, sponsored by Axway.

- This will require creating clear definitions, eg. limited = less than 3 apps available in each fintech category, emerging = 3-6 apps available in the geographic market, good availability = 7+ apps available in the geographic market.

- In turn, this will also require creating a standardised taxonomy for fintech apps and identify which type of fintech apps are most useful to each consumer segment.

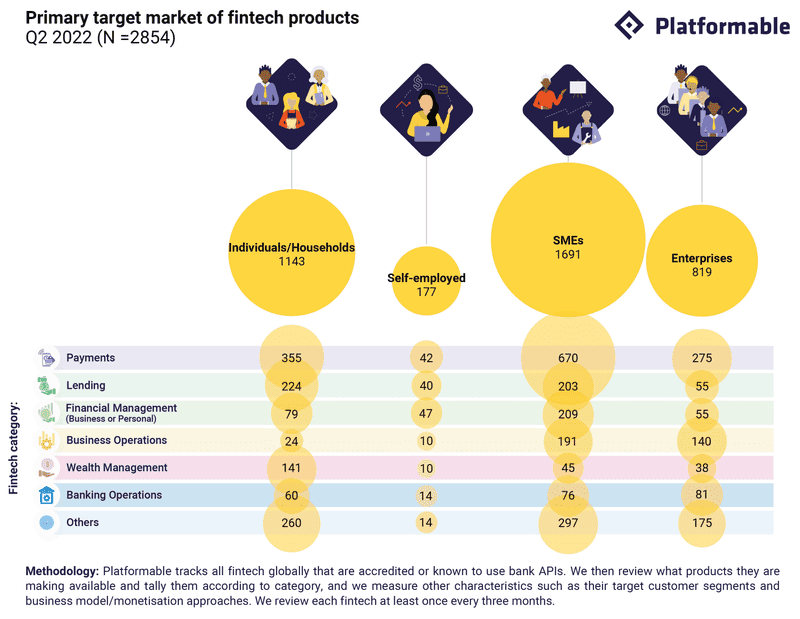

- It will also require defining each consumer segment. At Platformable, we categorise segments as: underserved (unbanked and underbanked), individuals/households, sole traders/self-employed/micro-enterprises, small and medium enterprises (SMEs), and large enterprises. Reynolds and Chidley provide further segmentation of individuals/household consumers into stratifications based on financial stability.

Increased financial inclusion

Potentially relevant datasets:

- Use cases of apps available to meet underserved populations (as shown on the CGAP API Dashboard)

- Number of individuals/households using fintech (that makes use of open banking APIs) that now say they can manage a financial emergency of up to $2,000.

- Number of adults opening bank accounts in the past month.

- Number of women, migrant-owned, Black, Indigenous, LGBT, and disability-owned businesses that are able to acquire appropriate lending via fintech services that make use of open banking APIs.

- This will require data on the number of businesses owned by women, migrants, Black, Indigenous or people with a disability.

Data on lending patterns from open banking APIs

We have found it challenging to uncover data on lending patterns in each jurisdiction. We believe that banking regulatory authorities should make data more accessible that shows lending patterns to the following consumer segments:

- Individuals/households

- Sole traders

- Small and medium enterprises

- Enterprises

- Non-profit and other entities.

For each of these segments, data should be disaggregated to enable analysis of:

- Annual incomes/revenue of each borrower

- Ownership of business/entity based on gender/sex, race/ethnicity, and migrant status

- Ownership of business/entity based on disability status.

For open banking, we then need to be able to see how much of this lending is occurring through open APIs. This needs to be disaggregated so that we can measure whether APIs are having an impact on reducing the structural inequalities and lack of access that have been embedded into banking systems over the past several hundred years.

In addition to these data sources that measure the opportunities that open banking is having for consumer segments, we also need new datasets that look at who is able to participate in building this new open banking ecosystem. Here, again, business registration data would be most useful. A report from the middle of 2020 from Crunchbase (an independently owned dataset on tech startups and other businesses and their investments) identified some of the under-investment trends facing women, Black, Latinx, LGBT and migrant-owned businesses. As a way to address this, Crunchbase’s CEO introduced diversity measures in August, enabling users of the business database to search for minority-owned businesses. This search feature was provided to encourage new investment: investors could quickly search women and minority-owned businesses and ensure they are included in their portfolio assessments. To date, Crunchbase has only enabled this feature for U.S. based businesses, and even then it is crowdsourced or comes from data provided by a small number of current investors, like Backstage Capital, which focuses on supporting startups initiated by women, Black and LGBT founders.

In Europe, there are standard datasets measuring the financing of SMEs, but because the underlying business registration data does not collect the characteristics of business owners, it is not possible to measure whether that financing is directed to all business owners or entrenching systemic inequalities. In an open banking context, it would also be good to see whether fintech is being created by women and minority populations, whether they are employed in management positions, and whether they are receiving the same levels of funding as white, male fintech startups. The European media outlet Sifted has done some excellent research and analysis on women’s participation in fintech, but this is often one-off research because of the lack of availability of structured, regularly collected datasets.

At Platformable, we are currently identifying whether there is women and non-white management participating in the fintech that use open banking APIs. We have a fairly crude measure: “If you are a woman or non-white potential employee, can you see that there are opportunities for advancement or participation in management by other women and non-white employees?” To answer this, we look at the “About the team” page of a fintech’s website or their organisational LinkedIn profile. It is embarrassing that that is our only potential measure to create a structured dataset at present.

Analysts, consulting groups, banks and fintechs themselves, and other commentators like to applaud the new opportunities that open banking can generate. But without these datasets that help us measure whether open banking is levelling the playing field, that’s a lot of currently unwarranted back slapping.